To be beautiful is to be perceived.

Beauty is to experience the emotions of reverence, wonder, and love at the sight or sound of that which we perceive as beautiful.

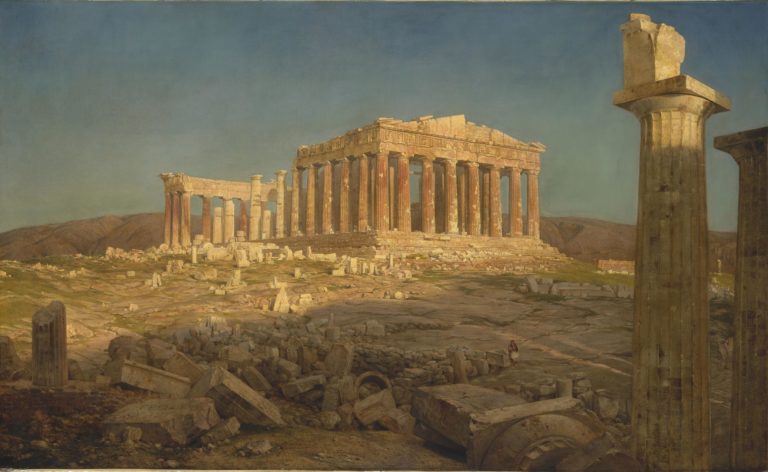

An expansive landscape; an intricate concerto; a healthy human form — all of these are “beautiful” to us because of how we feel when we see or hear them.

If beauty is that experience, then beauty cannot be an attribute inherent in the object.

A tree that falls in the woods still makes sound, even if no one is around to hear, because sound is a matter of physics. But a small tree clinging to life in the rocky mountains of China — the kind that eventually inspired the art of bonsai — is not beautiful until some literati takes the time to find it.

Until it is perceived, it simply is.

Whatever capacity the object has for beauty is latent, waiting for the light of mortal eyes.

Throughout time, people have tried to distill and crystalize “objective beauty.”

They have looked to symmetry, the golden ratio, and evolutionary history for some non-emotive core to an emotional experience.

And it is true that some traits lend themselves to beauty with greater universality than others. But just because something is universally beautiful to humans does not mean that it is beautiful in accordance with the laws of the universe. Humans are only a small part of that.

The golden ratio is mechanically functional in some places, but not in others. Same with symmetry: the human body is not symmetrical. Our right and left hands serve different purposes, corresponding with our right- and left-brain hemispheres. Our heart is on the left side of our body.

And evolutionary history can be useful for understanding the baselines of beauty, but many of the more complex and more powerful expressions of beauty are cultural in origin, not genetic.

Because beauty is an experience, it is subjective — not objective.

In The Bacchae by Euripides, the chorus chants:

ὅτικαλὸνφίλονἀεί

All that is beautiful is beloved forever

Philon (φίλον) is not just “beloved.” It implies a proximity and familiarity. Harvard philologist Gregory Nagy translates philon as “near and dear.” All that is beautiful is near and dear forever.

The “acquired taste.”

Philon means subjective knowledge — the priming and acclimation to know what you are looking at.

Euripides is saying that all that is beautiful is subjective.

But this subjectivity does not mean that beauty is arbitrary either. “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” doesn’t mean that everything is equally beautiful or has equal potential for beauty.

For something to be beautiful, it has to conform to and embody certain standards.

A piece of artwork or architecture which embodies a given standard with intricate simplicity may not be perceived as beautiful to someone who has not developed the taste for that standard.

But something which embodies no standard to any degree is ever going to be beautiful to anyone. Nothing is beautiful to everyone, but some things are beautiful to no one.

To the ancient Greeks, nothing was more beautiful than the tragic hero: the unseasonal man who embodied the most important qualities of his people… but perhaps too much. The hero suffers and dies not for his vices, but for his virtues. These virtues might be universal. All cultures across all time valued courageous men.

But the specific character of the hero — his idiosyncrasies and language and emotions — are not so universal. The hero must embody a certain aesthetic specific to his unique culture, claiming those virtues for that culture.

Or perhaps the story of the hero creates the aesthetic.

This is what we see in the history of Western heroism. An artist named Homer took the word “hero” — which meant “protector” — and transformed it into a concept of immortality.

The young aspiring hero performs great deeds in the service and protection of others, in hopes that stories and songs might carry his name into the immortal future long after his body is broken and devoured by dogs and birds on the field of battle.

The craftsman follows the standards of his trade to create beautiful things. His works are beautiful.

The heroic warrior internalizes these standards and embodies them in himself. He becomes beautiful.

But for either of these to be possible, there must be a law-giver — the one who creates the standards.

Just as the sun is hard to look at but permits other things to be seen, the law-giver is not as beautiful as the warrior, nor as fertile in creative energy as the craftsman. But without his vision and guidance, there would be no path towards refinement, integrity, and fulfillment for the warrior and the craftsman.

There is some overlap in these categories. Hector was a warrior, but the standard set by his example paved the way for all of European chivalry — he is known as the first “paladin.” Homer was a poet, a craftsman of sorts, but his skill set the standard for future poets and storytellers:

It was Homer who gave laws to the artist; it was Homer who inspired the poet.

— Francis Wayland (1922)

The solar man is the law-giver, the one who gives comprehensibility to his world. He is the sun by which others can be seen and known.

And the vision of the solar man is the light by which beauty enters the world.

He depicts a world and others circle his brightness, emulating, expanding upon, and refining what the solar man set into motion. Solar vision creates the possibility of beauty, the subjective standard laid down for other men and for women, by which they can progress in creating beauty and becoming beautiful.

C.B. Robertson is the author of Letter to Anwei, Holy Nihilism, and The Hero and the Man. He lives with his wife and children in the Inland Northwest.